For global health to truly deliver the overarching aim of health equality for all, it must overcome the artificial dualism separating mental from physical illness, in line with the WHO definition of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’

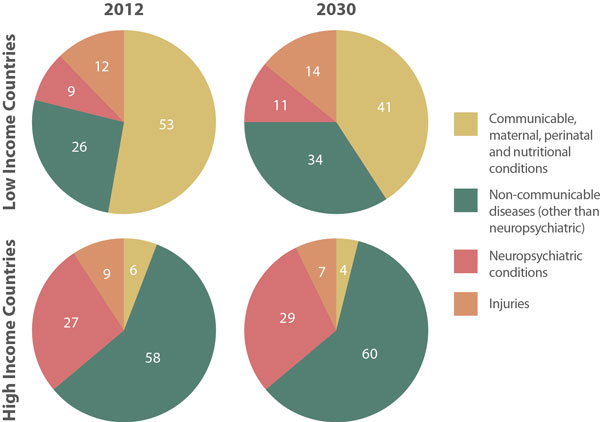

Globally, mental health is stigmatised and neglected, with a greater focus placed on infectious diseases, maternal and child health in the developing world and on other non-communicable diseases in the developed world. This creates an enormous treatment gap in some countries, with up to nine out of ten patients not receiving basic care.

The lack of correlation between services and disease burden, low numbers of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses and migration of trained staff are key challenges to addressing mental health inequalities in developing countries.

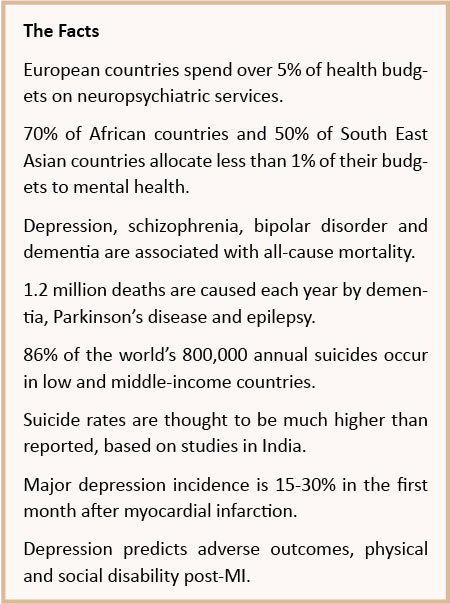

Although their treatment is under-prioritised, the contribution of neuropsychiatric conditions to the global burden of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs: years lived with disability plus years of life lost) is growing. The greatest proportion (28%) of worldwide non-communicable disease burden is attributable to neuropsychiatric conditions, with 10% contributed by unipolar affective disorder alone, and there is a clear correlation between neuropsychiatric DALYs and economic development. As lives lost to communicable diseases decline with improved sanitation, nutrition and healthcare, the contribution of neuropsychiatric conditions to worldwide disability increases.

No Health without Mental Health

Despite the traditional separation of services for physical and mental illness, there are complex inter-relationships between the two, encapsulated in the phrase, “no health without mental health”. This oft-ignored fact was discussed in depth in the Lancet’s first global mental health series in 2007.

An in-depth database search published in the Lancet revealed the relationship between global mental health and broader physical health and concluded that:

Mental disorders increase risk for communicable and non-communicable diseases, and contribute to unintentional and intentional injury. Conversely, many health conditions increase the risk for mental disorders, and comorbidity complicates help-seeking, diagnosis, and treatment, and influences prognosis. Health services are not provided equitably to people with mental disorders, and the quality of care for both mental and physical health conditions for these people could be improved.1

These authors highlight the role of stigma in the justification of ignoring mental health needs, and the isolatation of psychiatric treatment from the rest of medicine, despite their evident inter-relationship. The relationship between physical and mental illness, mortality and morbidity is complex and bidirectional, affecting rich and poor countries alike.

Despite the traditional separation of services for physical and mental illness, there are complex inter-relationships between the two

2.6 million people were newly infected with HIV in 2009. Symptomatic HIV is associated with poor mental health via direct impact on the central nervous system, as well as via opportunistic infections and antiretroviral side effects. Crucially, depression, cognitive impairment, alcohol and substance-use disorders reduce adherence to HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy), increasing drug resistance. HIV cannot be treated in isolation; whilst collaborative interventions now target tuberculosis and HIV together, these must also incorporate neuropsychiatric services.

Despite the absence of mental illness from the Millennium Development Goals, global mental health plays a role in their achievement. Women have a 1.5-2.0 times greater risk of mental illness than men, mediated by poverty. Mental disorders are correlated with gynaecological morbidity, including chronic pelvic pain, whilst maternal psychosis is associated with preterm delivery, low birth-weight, stillbirth and infant mortality.

Poverty and Mental Health

It is clear from the literature that the Millennium Development Goals: combating HIV/AIDS, gender equality, child health, maternal health, ending poverty, universal education, environmental sustainability and global partnership are all directly or indirectly related to improved mental health. Studies implicate the need to integrate mental health treatment and promotion into primary and secondary general healthcare, and to maximise physical and mental wellbeing in settings where psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses are in short supply.

There is evidence that the social, psychotherapeutic and behavioural support of community clubs has increased compliance, treatment completion and cure rates for tuberculosis in India and Ethiopia. Service user networks in Zambia show how campaigning, community action and self-help in the voluntary sector can complement statutory services.2 For example, workers actively contact mental health service users, supporting them and their carers, targeting cultural beliefs in bewitchment and possession and social stigma. Provision of community mental health services would cost US$2-4 per person, per year in low to middle-income countries,3 a worthwhile investment given the cost of disease burden.

Women have a 1.5-2.0 times greater risk of mental illness than men, mediated by poverty. Mental disorders are correlated with gynaecological morbidity, including chronic pelvic pain, whilst maternal psychosis is associated with preterm delivery, low birth-weight, stillbirth and infant mortality

Through apprenticeship models and practical toolkits for well-trained and supported lay workers, there is scope to greatly expand mental health human resources to increase access to high-quality care.4 Furthermore, lessons learned from the developing world may be transferrable to the under-provision of mental healthcare in the developed world, and may be a key force against worldwide stigma:

Non-specialist health professionals, lay workers, affected individuals, and caregivers with brief training and appropriate supervision by mental health specialists are able to detect, diagnose, treat, and monitor individuals with mental disorders and reduce caregiver burden.5

In the UK, moves to Improve Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) have led to the training of other professionals in the skills of cognitive behavioural therapy. Similar initiatives have shown promise in developing countries including India, Pakistan and Uganda. Psychological treatments for depression, adapted to the specific community’s cultural context, delivered by lay and community health workers showed significantly increased recovery rates compared with treatment as usual. These studies simultaneously addressed human resource and acceptability barriers to accessing psychological therapies in the developing world.6 Their encouraging results are attributable in great part to rigorous training, support and supervision provided, and should not be seen as alternatives to the provision of highly skilled psychiatrists, psychologists and psychiatric nurses, indispensable for the care of severe psychiatric illness.7

No Stigma in Mental Health

The Movement for Global Mental Health’s call for action makes five recommendations.

1: All governments deliver a national mental health service.

2: International donors prioritise mental health in resource allocation to low and middle-income countries.

3: US$2-4 per person be the minimum budget for mental healthcare.

4: Budgets are transparently monitored.

5: Research prioritisation and dissemination of findings. In a promising move, the UK recently unveiled a doubling in funding for research

into dementia to £66 million by 2015.

These proposals make economic as well as clinical sense. Two systematic reviews found that mental health interventions are associated with improved financial outcomes: evidence that neuropsychiatric conditions must be a priority of development interventions.8

Pervasive stigma and discrimination towards mental illness continues to cause widespread human rights abuses towards people with neuropsychiatric disorders worldwide

Importantly, pervasive stigma and discrimination towards mental illness continues to cause widespread human rights abuses towards people with neuropsychiatric disorders worldwide. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities advocates a collaborative approach to address stigma. This should involve all stakeholders in education, empowerment and accountability, which have been instrumental in reducing stigma surrounding HIV and other disorders:

This begins with educating all parts of society, including all sectors of government, health and mental health professionals, the media, and of course people with mental and psychosocial disabilities and their families about mental health and human rights […] Civil society must be enlisted as advocates and agents for change, holding governments accountable for meeting their obligations [...] To rectify this historic and ongoing neglect and mistreatment, it is essential to create clear benchmarks or indicators of tangible progress, with rigorous monitoring and assessment at the state and international level.9

Stigma must be addressed if governments are to invest precious resources in global mental health and for society to support its prioritisation. Four years on, the movement has seen progress in its recommendations. The second Lancet series in 2011 outlines this, but stresses the continued need to implement these goals. Health and social policy must use the existing strong evidence base to support critical investment in developing countries. Here, the collaborative ethos of global health can be extremely effective, integrating multidisciplinary clinicians, lay persons, service users and carers in a highly motivated workforce. Only through this unified approach can global healthcare deliver its goal: complete physical, mental and social well-being, for all.