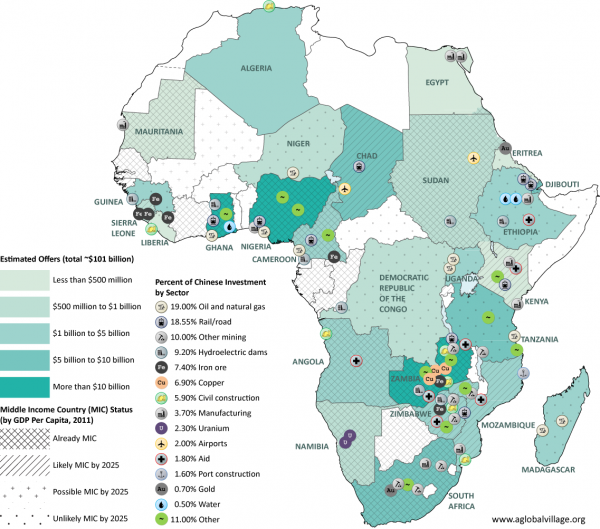

According to the International Monetary Fund, seven of the ten fastest growing economies over the next five years will be in Africa, a figure which is starting to capture the attention of both private and institutional investors. The Chinese, who have heavily invested in the continent over the past decade, appear to be planning to stay for the long-haul. Is this a sign of confidence that Africa will emerge as a legitimate force in the global economy?

Emerging markets was a term originally coined in 1981 by the Investment Manager and World Bank Economist Antoine van Agtmael to lift the negative connotation attached to the expression ‘Third World Country’. As one of the first investors to recognise the financial potential of developing countries, his idea for a ‘Third World Equity Fund’ was instantly met with scepticism from leading investment managers. “Racking my brain, at last I came up with a term that sounded more positive and invigorating: emerging markets. ‘Third world’ suggested stagnation; ‘emerging markets’ suggested progress, uplift and dynamism.”1

Originally, emerging markets were defined as economies with low-to-middle per capita income. Today, some of these countries such as Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea, known as Asian Tiger states, could be considered to have emerged and are now highly developed economies. These have been closely followed by the BRIC economies who have experienced unprecedented growth over the past decade, with China on a path to overtaking the USA as the next economic superpower.

Given their generally high growth rates, ‘emerging’ as a description for this group of countries may still be adequate in the classical sense of the word, but perhaps today’s true investment opportunities lie at a new frontier - Africa. Wolfgang Fengler, the World Bank’s Lead Economist in the Nairobi office is positive, “It is very possible that several African countries will follow in the footsteps of the BRICs and reach similar levels of income.”

Sustainable Investment

With a total population of more than one billion spread over 54 nations, and rich natural resources distributed across 12 million square miles, Africa has always attracted more adventurous investors – but can it lure the mainstream?2. Rajiv Jain, fund manager at Virtus, an asset management company, is not convinced, “You cannot put serious money to work in these economies.”

With an average growth rate of 6%2 (excluding South Africa, which represents a third of Africa’s economy), GDP growth in the African region is substantially above the rest of the world, and the debt-to-GDP ratio is low as a consequence of debt forgiveness offered to African nations in the early 2000s. The comparably strong performance of emerging market funds during the recent global economic crisis highlighted the advantages of clever niche investment and, in general, higher volatility of African financial instruments can be offset by diversification as Africa’s markets are little correlated with other global markets. Investors are becoming more aware of the profits to be made, but there is a lingering reluctance to invest in the region.

According to Wolfgang Fengler, the reason African financial markets and their expanding public companies are still relatively unknown and under-invested is that the base is still too small. “Africa has yet to reach critical economic mass on most accounts. No country except Nigeria has a population of above 100 million. As a result, doing business in Africa is only interesting if companies can tap into larger regional markets. This is why regional integration is so important.”

There is a well-established route via which more developed states indirectly invest inAfrica. Development aid, however, is often criticized for being ineffective and an easy target for corrupt officials. Could Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) become a sustainable and bi-directional complement to traditional development aid?

Wolfgang Fengler urges policy-makers to think of development aid not just in terms of money, but as a tool to generate knowledge transfer and international learning. “As more African countries are reaching Middle Income Status, the role of aid to Africa will fundamentally change – or it becomes irrelevant.” In fact, in many African countries FDI already has a larger volume than aid, with the main investor being China.

The Chinese in Africa

A highway across the African continent, from Cairoto Cape Town, was once the dream of colonial rulers. Today, this highway is being built by China. In fact, in many African countries still lacking modern road and tranport links, the Chinese have seized an opportunity to drive infrastructural development, and currently hold more than 50 % of public contracts in Africa.5

With extensive investment in infrastructure, roads, railways, ports and airports all across the African continent, Chinais unblocking major bottlenecks to growth. The rehabilitated 840-mile Benguela railway line, for example, now connects Angola’s Atlantic coast with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, and bilateral trade between China and Africa reached $160 billion in 2011, up from just $9 billion in 2000.6 Whether interpreted as disguised neo-colonialism to secure Africa’s vast reserves of natural resources, or shrewd business strategy, Chinese investment has become a significant catalyst for economic development in Africa. Can Africa drive a transformation similar to the Chinese success story?

In fact, in the early 1980s most of Africa was still richer than China. Only 30 years ago, China was mainly considered to be a source of cheap labour for the developed world, however, with huge success in the manufacturing industry and consequent growth,China, is becoming increasingly expensive. Today, “Africa has a great opportunity to enter the segmentsAsiais leaving behind and take off,” argues Wolfgang Fengler.

The key to China’s success in Africa is strategic long-term planning - in contrast to Western portfolio investors who tend to flee as soon as difficulties arise. An example of the Chinese business model is their presence in the Republic of Zambia. As the world’s largest copper consumer, China needs copper almost as much as it needs oil and Zambia, with its rich copper resources, is one of China’s most important partners in the region. Step by step, Chinese entrepreneurs have bought nearly all existing Zambian loss-making copper mines, investing more than 1 billion dollars.

However, working conditions and cultural conflicts regularly make the headlines. Imposition of the Chinese one child policy in many Zambian copper mines, for example, has evoked a lot of criticism. “Health insurance coverage is only provided for the first child. As a Zambian, my culture allows me to have many children. We are Africans, and this should be respected,” criticises a Zambian copper mine worker.5

Yet overall, the reaction to the Chinese presence in the country is positive due to the jobs created and significant impact of the infrastructural development. Li Qiangmin, Chinese Ambassador to Zambia, sees their strategy as a win-win model. “Our experience with foreign investment as a developing country in the past has influenced our policy in Africa. Moreover, our economy experiences enormous growth. We are looking for outlet markets and raw materials in Africa.”5

Trade, not Aid

Besides Zambia, another major recipient of Chinese investment is Kenya. Hoping to copy the efficiency of Chinese companies in Africa, Wahome Gakuru, director of Kenya’s 25-year economic plan, Vision 2030, sees great potential in outsourcing Kenya’s infrastructure. “From Chinawe want a transfer of skills: how to build roads, bridges, teaching discipline,” he said.7

In November 2012, three Chinese companies successfully completed a Kenyan superhighway linking Nairobiwith the city of Thika. The road, 8 lanes wide, is the biggest of its kind in East Africa.8 Helmut Reisen, lead economist at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), says “Africa presents at the moment a division of labour that can only displease the West. China is responsible for promising economic projects and cooperation, while the West takes care of humanitarian and social projects.”5

The Chinese have seized an opportunity to drive infrastructural development, and currently hold more than 50% of public contracts in Africa

Despite fifty years of development aid, sustainable growth has not been generated but rather a dangerous dependence on donor countries has developed, explains Kenyan economist James Shikwati. “When politicians draw sustenance from donors, they have to give account to the World Bank, the IMF and the international donor community, and they tend to pay less attention to the desires of their own people.” Only time will tell whether the alternative Chinese approach to investment reverses this trend towards more independent and sustainable economic governance.

Changing Demographics

Growth in Africa is driven by its demographics. “Development is ultimately about people. If people live longer, and closer together, countries can benefit from a demographic and geographic dividend. They are then more likely to have higher incomes which is spent on fewer children. With a better upbringing, these children then have better opportunities than their parents. This creates a virtuous economic cycle which we are currently observing in most ofAsia”, explains Fengler. If Africa manages this demographic transition well, it can expect to see in the next 30 years what Asia experienced in the last 30 years.

However, Africa’s challenges are well documented. Lack of liquidity, insufficient infrastructure, healthcare, political and social instability as well as corruption are just some of the major roadblocks that hinder development; African countries have yet to transform their economies as the BRICs have done. “The best example is the weakness in manufacturing. As long as African countries don’t produce industrial goods for the global market on a global scale, they will remain behind the BRICs,” predicts Fengler.

Furthermore, while most African countries are expected to have reached middle-income status by 2025, these statistics often disguise wide discrepancies as the benefits of accelerated growth are often concentrated in the hands of a few. Fengler warns of misconceptions, “If a country becomes a middle-income country due to a sudden discovery of natural resources it often does not change anything! The realities of the average and poor person remain dismal and sometimes natural resource discoveries make their lives even harder, especially if these new resources are not managed well as in Congoor in Gabon.”

Nevertheless, Fengler sees Africa on the rise. “The continent has a great opportunity to benefit from a combination of several big trends: The demographics are favourable, urbanization creates new economic dynamism and technology has also empowered the poor in a remarkable way.

“Now comes the hard part: economic transformation has yet to happen and will depend on countries tackling their deep-rooted governance issues”, says Fengler, “Only then Africa will be able to claim this century.”