Imagine trying to attend classes in these schools while you have your menstrual period. Imagine your menstrual period is extremely painful. Imagine your reuse-able pad is soaked through but there is no running water to clean it, or that there is no trash bin for disposing your used pad. Imagine having your pad soaked through to your pants so you have to hide the stain with your book bag. And don’t forget this happens every month.

Sadly, adolescent girls in the developing world do not have to imagine these situations. They experience it every year, even every month – if they manage to stay in school. Many are not able to stay in school after too many missed classes, too many embarrassing moments, too many failed tests, too many repeated grades and too many disappointments.

Analysis of the Millennium Development Goals (MGD) indicates that the education sector goal of universal education (MDG 2) will not be achieved by 2015. Tremendous progress with child school enrollment has been made, and the current global rate is at 89%; however it has plateaued since about 2004. Beyond enrollment in school, children need to complete their schooling to benefit from this access, however, in some regions such as Africa, 30% of children drop out before they complete their primary school education.1 Equally enrollment parity between girls and boys has not yet been achieved, although we are closer than ever before, and gender equity decreases at higher levels of schooling.

The reasons for low enrollment and incompletion of education are numerous, but the health and nutrition status of the children are critical factors. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 272 million school days are lost each year due to diarrhea alone and about 400 million children in the developing world have worms that prevent them from learning.2 These barriers to education are further exacerbated with puberty. Adolescence brings with it rapid biological changes including the development of reproductive capacity and changes in the sexual response system. Adolescence is also a critical time for cognitive changes that lead to the emergence of advanced mental capabilities, such as increased capacity for abstract thinking and empathy. It is also the time for major social-emotional changes as children transition into adults and shift from dependency to interdependency within their society.

Yet most boys and girls are unprepared for these changes; some studies indicate that around 66%3 of girls know nothing about menstruation until they start their menses, which makes for not only a negative, but also a traumatic experience. The lack of knowledge and skills for menstrual management can be detrimental to school attendance, quality and enjoyment of learning for girls. According to UNICEF4 1 in 10 school-age African girls ‘do not attend school during menstruation, or drop out at puberty because of the lack of clean and private sanitation facilities in schools’. In another survey conducted by FAWE in Uganda, 94% of girls reported issues during menstruation and 61% indicated missing school during menstruation.5 According to Water Aid, “95% of girls in Ghana sometimes miss school due to menses and 86% and 53% of girls in Garissa and Nairobi (respectively) in Kenya miss a day or more of school every two months. In Ethiopia 51% of girls miss between one and four days of school per month because of menses and 39% reported reduced performance”.6

Girl Troubles

For girls, in particular, the impact of low school attainment and poor health and nutrition can have a magnified impact on the next generation. Malnourished girls become mothers who face high levels of maternal mortality, and bear low birth weight babies. In addition, the link between female educational attainment and lifetime health is unequivocal; a better educated girl takes better care of herself and as a woman, has healthier and fewer children.

Save the Children’s experience in Ethiopia illustrates these health issues and provides evidence of what can be done to ensure adolescent girls stay in school. Girls in Ethiopia navigate puberty without proper information about the physical changes they can expect, without support from family members, without schools that have a “girl-friendly” water and sanitation infrastructure, and without information on feminine hygiene products. Ethiopian adolescents have limited access to sexual and reproductive sexual health information and services, and the sociocultural context perpetuates an environment in which these issues remain taboo to discuss with parents.

Within this context, Save the Children has been working in Ethiopia since 1998 to improve adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health with comprehensive, multifaceted programs. More recently, the organisation began to pay particular attention to the needs of girls in their early adolescence who were making the critical transition from primary to junior secondary school. There is a particularly high dropout rate and declining school attendance at this stage. The Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) programme was designed to identify these issues via a qualitative study (including forty-nine girls, forty-seven parents, and fifty-two teachers). The results concluded that:

- Information on reproductive health is very limited – particularly on puberty, feminine hygiene, and menstruation. A few girls reported receiving some information on reproductive health and puberty from science and biology classes.

- Girls learned about feminine hygiene from peers and sometimes from elder sisters and mothers. Many experienced their first period on their own without prior information about the onset and nature of menstruation.

- Many girls were surprised or panicked by their first menstruation.

- Some girls described not wanting to go to school when menstruating because they felt they could not fully participate in school activities.

- Girls, teachers, and parents all agreed that girls’ menstruation and related issues have an effect on school performance and attendance.

- Most of the girls use cotton or cloth from old dresses as sanitary protection materials and complain about their lack of comfort and inadequate protection quality. Only a few described having used commercially produced sanitary pads.

- Most girls, particularly those in rural areas, had never seen sanitary pads, although most had heard about them. Almost all girls were enthusiastic about learning about these alternative menstrual blood management products.

- While participants said they looked forward to the opportunity to use sanitary pads, they also expressed concern about sustained usage due to cost.

- Girls stated that school latrines have limited privacy and poor hygienic conditions. Teachers and girls also confirmed that there are no hand-washing facilities at the schools.

Girl-Friendly Schools

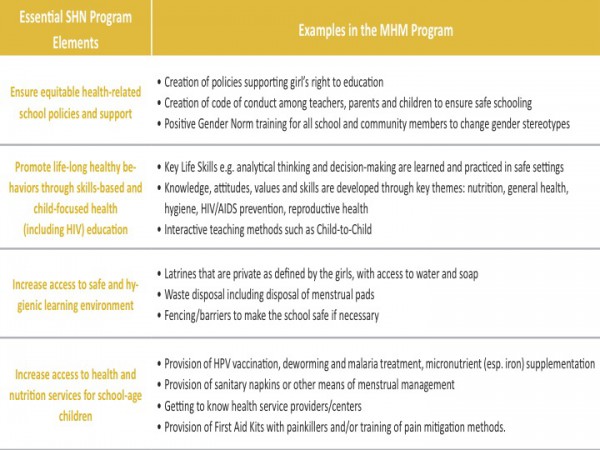

Based on these results, Save the Children developed a four-part programme using the School Health and Nutrition (SHN) programming framework. SHN addresses the critical health, hygiene and nutrition factors that keep children and adolescents out of school and reduce their ability to learn.

First, it created community dialogues and community spaces where mothers, teachers, community leaders, and girls could come together to talk about puberty and menstruation in order to begin breaking down taboos that prevented discussion of these issues. The conversations helped families and teachers begin to understand the challenges that adolescent girls face in school when they are menstruating, and together are now finding ways to make communities and schools more girl-friendly. For example, once communities recognized that menstruation was not initiated by sex and that the girls needed assistance, the parents helped build better latrines and sought out local materials for sanitary pads.

Many schools in Ethiopia have no bathrooms or latrines

Second, a school-based sexual education programme was developed to teach adolescent girls about puberty, menstruation, and menstrual hygiene. They linked this effort to a broader curriculum for very young adolescents in which girls also learned about the risks of early marriage and preventing pregnancy, coupled with other life-skill–building exercises, to help them negotiate a healthy adolescence. Teachers and girls’ peer leaders were trained to roll out this life-skills curriculum as an extracurricular learning opportunity.

Third, Save the Children collaborated with communities to improve the water and sanitation infrastructure within schools. Unfortunately, too many schools in Ethiopia have no bathrooms or latrines. Girls describe such an environment as being unsafe and undignified. The new latrines designed by the girls are separated from boys’ latrines and have doors that lock from the inside, as well as a place to dispose of menstrual hygiene materials.

Fourth, the girls were introduced to all the menstrual hygiene products available to them including both traditional and commercial products. Girls in the programme were provided with a three-month supply of sanitary napkins to help them understand the different methods of menstrual blood management.

The success of this multi-sector programme depends on effective partnerships between education, health, and other sectors, as well as with communities and with children and adolescents. Save the Children’s implementation approach is to create model programmes through strong partnerships with governments, local organizations and communities. The engagement of communities is especially critical when challenging current gender norms and addressing reproductive health issues. Mobilizing and educating parents and community leaders were necessary for the success of these projects and should be the first step in future efforts to address the needs of girls in and out of schools.