Increasing life expectancy and a greater number of older people are powerful signs of progress. Advances in science and medicine over the last 50 years have led to substantial declines in the number of deaths from infectious diseases and malnutrition. But ageing populations also pose important challenges for societies around the world by putting substantial pressure on healthcare systems to reform.

Older people require a different type of care than the rest of the population – with conditions typically requiring management, rather than treatment. This, combined with rising demand from a greater number of older people with higher expectations of care and falling supply of both formal and informal care, is leading to health and social care services that are ill-equipped to deal with these demographic developments.

Today too little is being spent on the ‘basic’ primary care that older people often require and, where care is provided, it is often done so in a disjointed fashion. Getting the correct funding mechanisms in place, improving the flow of patient information and better co-ordinating care is crucial if societies are to deal with the challenges posed by ageing societies.

There are currently 800 million people aged 60 years and up, making up 11% of the world’s population. By 2030 they will number 1.4 billion and make up 17%. In 2047, for the first time in human history, a higher proportion of people in the world will be aged 60 and over (21.0%) than under 15 (20.8%).1 Ageing is affecting all countries, both high and low-income. Lower life expectancy disguises the fact that there are many older people in developing countries, and by 2050, 68% of the world’s over-80 population will be living in Asia or Latin America and the Caribbean.

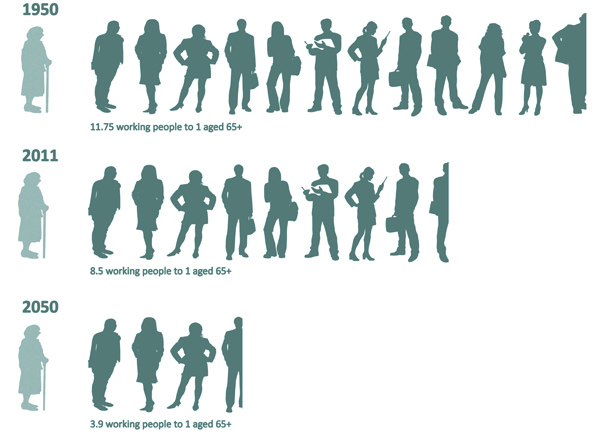

There will also be fewer working age people per older person. By 2050 there will be just 3.9 people of working age for each individual over 65. This matters, not just because healthcare funding is drawn from the working age population, but also because it means that there will be fewer people to be the carers and doctors.

Does older mean more expensive?

During a typical person’s lifetime their healthcare costs will be greater the older they get. However this does not necessarily imply that the total cost of healthcare increases as people live longer. In fact research has shown2 that ageing has only had a small impact on overall health expenditure. Instead it is proximity to death, rather than age, which is the most accurate predictor of healthcare expenditure. Several non-demographic factors, notably per capita income, medical technology and workforce costs, are also thought to have a stronger impact on increases in healthcare expenditure than ageing.3

Unlike life expectancy, the way people age makes a big difference to a population’s healthcare bill. If a longer life means more time spent in ill-health costs will rise. However, if the extra years are spent in good health, expenditure remains steady or can even be reduced. The so-called ‘compression of morbidity’ – minimising the time people spend in sub-optimal health – is therefore an important aim for societies as their populations age.

Caring for Non-Communicable Diseases

Today the demand for care is increasing, driven by larger elderly populations, increasing levels of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and higher expectations of the quality and quantity of care that individuals wish to receive, in particular in high-income countries.

Simultaneously the supply of care is falling. Informal caring arrangements – care provided by a spouse, family or children – are critical to many older people. It has been estimated that the care provided by informal carers in the UK is worth £119 billion per year4 – the same as all traditional healthcare spending combined. However, four global trends are leading to a dramatic decline in the number of informal carers: increased female education and participation in the workforce; migration and urbanisation; declining fertility rates; and, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the HIV/AIDS epidemic which has led to ‘orphaned’ parents. Formal care is also being squeezed due to a shrinking pool from which to draw carers and clinicians due to the lower ration of working age to elderly populations described above. Finally, older people tend to suffer from a greater number of conditions simultaneously. This creates demand for a different, more holistic, type of care than that required by the younger population that will typically suffer from for a single, isolated disease.

Ageing has only had a small impact on overall health expenditure. Instead it is proximity to death, rather than age, which is the most accurate predictor of healthcare expenditure

Some conditions are primarily associated with old age, such as dementia. There are an estimated 35.6 million people living with dementia worldwide, with the number set to double every twenty years to 115.4 million in 2050. Among people aged 60 and above in high income countries, Alzheimer’s and other dementias account for 9 per cent of healthy years lost to premature death or disability, the largest share of any single NCD.5 However, it is not just a high-income country issue as two thirds of people living with dementia are doing so in low and middle income countries. Old-age conditions like dementia typically need to be managed rather than treated – requiring care, rather than healthcare.

These three key trends – increased demand from a larger number of older people with higher expectations of care; reduced supply of both informal care and traditional care; and a shift in demand to management rather than treatment all imply that health and social care services – in particular in the UK, but also elsewhere – are ill-equipped to deal with the pressures of an ageing society.

Coordinating Care

As the pool from which workers are drawn shrinks, it will become more important than ever to ensure that the right type of care is provided at the right time in the right place by the right people.

Too much money is spent on secondary care (the type typically provided in the hospital setting) as nearly two thirds (65%) of people admitted to hospital in the UK are over 65 years old. Many of them would not need to be there if proper care and support were provided outside the hospital such as that provided by district nurses that might include help eating or ensuring medicines are taken correctly. This leads to massive waste as basic care is delivered by highly paid specialists.

Studies suggest that as many as 40% of patients who die in hospital do not have the medical needs that require them to be there.6 Less than 20% of people die in their own homes even though most people would prefer to do so. As the focus shifts from curing patients to managing their conditions, hospitals look increasingly poorly equipped. Resources need to be re-allocated from hospitals to long term care, provided by the community and general practice.

More needs to be done to enhance existing services and to create new ones capable of dealing with the higher expectations people have of them. Carers, many of whom are old themselves, require support to ensure they do not become overburdened by, for instance, providing them with respite assistance. Primary care (and community care) needs to be available at weekends and at night to ensure that people are not in the position of having no alternative but to go into hospital to seek care.

As well as more care being provided outside of hospital, all care – whether it be specialist, primary or social – needs to be coordinated around the patient. Healthcare, mental healthcare and social cares are currently delivered separately, with little integration. Older people, more than the rest of the population, often require two or more out of these.

Old-age conditions like dementia typically need to be managed rather than treated – requiring care, rather than healthcare

Integration of care within the hospital is just as important. As argued in a paper by the Royal College of Physicians,7 organ-based specialties which have, in the past, led to significant improvements in clinical quality are now causing issues as older patients (who typically have more than one condition) are passed around between specialties with insufficient coordination. For care to be delivered in the optimum location and for care to be better coordinated, two key things need to change: funding and the flow of patient information.

Reimbursement needs to be designed and implemented on a ‘whole system’ basis and over a sufficient period of time to incentivise care to be delivered by the most appropriate person, at the most appropriate time, in the most appropriate place. Such capitation budgets would cover a population for their entire healthcare, mental health and social care needs and would reflect the risk profile of the population being covered. Only once these budget components are combined can a proper distribution be made to services based on the value they create for the patient.

Information about the patient’s needs and what care and treatment is being given needs to be available to everyone involved in the whole of the patient’s pathway, in real-time. The patient must also be able to provide feedback – both their impression of the outcomes and their experience of care delivery. This input should be used for continuous improvement in the system. A good example of where a version of this is being implemented is the North West London Integrated Care Pilot, which is integrating the care record between secondary, primary and social care for patients with diabetes and the over 75s. However, this needs to be taken further to give the patient access to, and the ability to interact with, the record and expanded to include more information, accessible in real-time.

Ageing populations will create significant challenges for societies and how we fund and deliver all types of care. But the pressures they create may also hasten the move to a more patient-centric approach that is better able to keep people healthy, rather than just treating them once they fall ill. This coordinated approach will benefit the whole population, young and old.