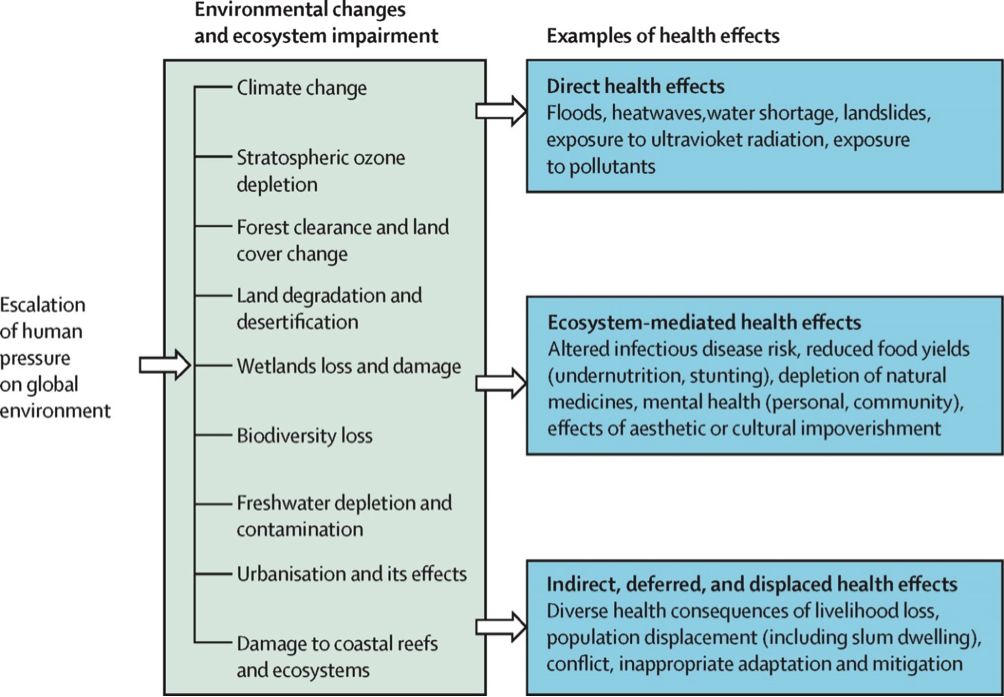

The large extent of our debt with Nature is likely to have important repercussions on our health. A number of health outcomes are potentially affected by environmental and climatic changes. The most common and well-studied among these outcomes are premature deaths related to heat waves, the consequences of floods and drought, and the changes in the habitats of disease vectors spreading malaria and dengue. Yet, a range of other unforeseen impacts are likely to occur, such as volatile food prices and wildlife decline affecting nutrition, and a rise in salinity leading to widespread hypertension.

Can synergies or 'co-benefits' arising from currently independent efforts to tackle climate change issues such as energy use, agriculture, food production and transportation also mitigate some of it's health effects?

The recent Lancet-Rockefeller report on planetary health1 draws our attention to the enormous debt that humanity has contracted with the environment. In the case of the economy, most human activities are currently based on loans from Nature, the extent of which has not yet been quantified. The overall monetary debt in the world has been estimated to be 200K billion dollars, corresponding to 286% of the overall Gross Product. But the debt towards Nature (due to the loans in kind) is likely to be much larger. The use of land and the related erosion and impoverishment, the misuse of water, fisheries or the atmosphere, just to give some examples, are creating a debt with Nature that cannot be returned, not even within decades.

The varied aspects of the environmental crisis have just started emerging, as the report from the Lancet-Rockefeller Commission has clarified1. Here we examine some of the large number of health outcomes that may be affected, as diverse and novel issues emerge as a result of the unpredictability associated with climatic change.

Unforeseen issues

Many consequences of climate change are likely to affect the amount and quality of food or water available to the poorest populations, as the following examples suggest.

The price of bread

A potentially devastating problem related to globalisation and exacerbated by climatic change is represented by excessive fluctuations in food prices. Primary goods, such as food, are subject to the financial drift of the economy. This, together with a dependence on food imports, leads to fluctuations in prices that especially impacts on poor countries.

For example, during the Russian drought and heatwave of 2010, 17% of the total crop area of the country was affected causing a national decline of 33% in the wheat harvest. As a result, a ban on wheat export was implemented that led to a 60–80% increase in global prices in the summer of 20103. This resulted in major increases in wheat and bread prices, in major importing countries such as Egypt, Syria and Yemen.

The problem is also related to the financial drift of the economy that is the fact that primary goods such as food are subject to financial speculation. This – together with dependence on food imports - leads to fluctuations in prices and increases the weakness of poor countries.

Empty forests

Wildlife decline threatens human nutrition throughout the developing world, where protein intake is often dependent on hunting. On average, populations of vertebrate species have declined 50% globally since 1970.

A prospective longitudinal cohort study of preadolescent children in rural Madagascar showed that consuming more meat from wildlife was associated with significantly higher haemoglobin concentrations. Modelling by the same authors suggested that loss of wildlife would cause a 29% increase in the numbers of children suffering from anaemia3.

The consumption of wildlife is a very important source of protein, and micronutrients and wildlife declines directly threaten the nutrition and health of millions. Low intake of micronutrients, such as iron and zinc, is also likely to occur due to other impacts of environmental change, such as soil impoverishment due to erosion, floods, drought or over-exploitation.

Salty seas

Land in deltaic regions is often very fertile and therefore is a popular place to settle for many inhabitants of India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. Studies have shown that the drinking water sources of populations in mega deltas, such as the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, are highly saline. With the forecasted trends on sea level rise and extreme weather events, salinity problems are expected to further increase and affect larger populations in the future. The salinisation of drinking water in these deltaic areas has been associated with increased blood pressure in pregnancy and in non-pregnant adults4.

Additionally, salinity problems in Bangladesh are hypothesised to be further increased by an ongoing dispute with India around the Farakka Barrage, which diverts a portion of the Ganges flow, and decreases the flow into Bangladesh. The analysis of data on pregnant women in Bangladesh showed that drinkers of tube-well and pond water (sources high in sodium) had significantly higher average blood pressure (4.85/2.30 and 3.62/1.72 mmHg respectively) than rainwater drinkers5. A longitudinal study among coastal participants undergoing adaptation measures showed that decreases in drinking water sodium concentrations were significantly associated with decreases in blood pressure5.

If salinity in drinking water is exacerbated further by climatic and environmental changes we can expect an epidemic of hypertension (a major cause of stroke and cardiovascular disease) in coastal populations of the world.

Co-benefits: the sum is greater than the parts

It is sometimes claimed that policies to directly address climate change are too expensive, and since their effectiveness is difficult to predict, the result can lead to further economic decline. However, the co-benefits of implementing climate change mitigation strategies for the health sector are usually overlooked. The synergy between policies for climate change mitigation in sectors such as energy use (e.g. for heating), agriculture, food production and transportation may have overall benefits that are much greater than the sum of single interventions6. Here I describe a few examples of climate change mitigation strategies that have important co-benefits for global health.

Walking to work

The transportation sector is often the single largest source of greenhouse gas emission in urban areas. Policy makers tried to reduce this emission by discouraging car travel and promoting other means of (active) transport, such as cycling and walking.

Physical inactivity is one of the leading causes of non-communicable diseases all over the world. It has been estimated that the combination of active travel and lower-emission motor vehicles would provide a significant health benefit, notably from a reduction in the number of years of life lost from ischaemic heart disease (10-19% in London, 11-25% in Delhi)7. Also obesity, which is one of the world’s most brazen public health problems, particularly the increased occurrences in children, could effectively be reduced by a more active lifestyle. A 30-minute walk to work could, on many occasions, be enough to even out small positive energy balances, while at the same time contributing to a reduction in CO2 emissions.

Cleaner cooking

Air pollution is the biggest environmental cause of death worldwide, with household air pollution accounting for about 3·5-4 million deaths every year8. Improving heating and cooking systems, for example by making them more efficient, reduces both energy consumption and air pollution.

Improved models of stoves (electrical vs biomass) allow for a 15-fold reduction in the emission of particles and other pollutants, thus contributing to decreased emissions in the atmosphere. Especially in developing countries, where old stoves are common, these improved models could also have a considerable positive impact on health. Cooking on simple wood or coal stoves is currently a major source of indoor pollution and increases risk of certain chronic diseases, such as COPD. The Indian stove programme installed 150,000 new stoves. This initiative led to the a reduction in air pollution, benefiting both the environment and preventing a large number of deaths from COPD and other diseases.

Veggie burger, please?

Meat production is highly inefficient in terms of energy use. It requires an extremely high use of water and land per unit of meat. One fifth of all greenhouse gases worldwide are related to methane production from livestock farms. Reduction of meat intake by consumers would lower meat production and is therefore often promoted as a valuable climate change mitigation strategy. A high intake of meat has been associated with increased disease risk, in particular for certain cancers and cardiovascular disease9. Reduced meat consumption could therefore also have a major impact on public health. It has been estimated that a 30% reduction in livestock production in the UK would reduce cardiovascular deaths by 15%10. This recommendation may seem in contrast with the suggestion above that the disappearance of wildlife can lead to deficiencies in children’s diet in poor countries. In fact these are two completely separate and different phenomena, one related to the overconsumption of meat from domestic animals in rich countries, the other a subsistence economy based on a poor diet where protein intake is dependent on hunting.

Renewables for easy breathing

Non-renewable energy production, for example coal burning, is a major contributor to worldwide greenhouse gas emissions. The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) 5th assessment report stresses that the main health co-benefits from climate change mitigation policies come from substituting polluting sources of energy for renewable and cleaner sources, with a considerable effect on the improvement of air quality.

Many countries have adopted policies to reduce polluting energy production and stimulate production of (renewable) energy through cleaner sources. For example, since 2000, the government in the Chinese Shanxi province has promoted several initiatives (including factory shutdowns) with the goal of reducing coal burning emissions. The annual average PM10 (particle matter) concentrations decreased from 196 μg/m3 in 2001 to 89 μg/m3 in 2010, which, as a matter of fact, is still very high for Western standards. It has been estimated that the DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years) lost in Shanxi had decreased by 56.92% as a consequence of the measures11.

Putting co-benefits on the table

The co-benefits from climate change mitigation for the health sector have not yet been completely identified or quantified. The topic does not appear on the priority list of political discourse. Relevant sectors, including those involved in non-communicable disease prevention 12, transportation, agriculture, food production and climate change13, still work separately, while collaboration would improve the synergy between health improvement and climate change mitigation and maximise benefits for both.

It is hoped that these issues will be considered at the Paris conference this year, and the term ‘co-benefits’ will become common language and feature in the political agenda.