The number of sexual violence crimes in times of conflict is high. Reports have noted a spike in sexual assaults against Syrian and Iraqi women, and a rise in the systematic targeting of women and girls in the Central African Republic and South Sudan. Yet, these crimes often go unprosecuted.

In order to tackle this rise, clinicians and healthcare workers need to take on a new role in providing forensic medical evidence, and working with legal advisors and law enforcement to end a culture of impunity. For this strategy to work, there needs to be a change in court proceedings, new technologies available to aid medical documentation and a breakdown in the legal barriers that have for too long allowed perpetrators of sexual violent crimes to remain unconvicted.

Though the exact prevalence and extent is unknown1, sexual violence often occurs during times of conflict either from opportunistic environmental conditions or from strategic intent to terrorize, expel, humiliate, or subjugate victims and their communities2. An urgent response is critical in light of recent reports about Islamic State attacks on Yazidi women, and Taliban attacks in Kunduz, Afghanistan.

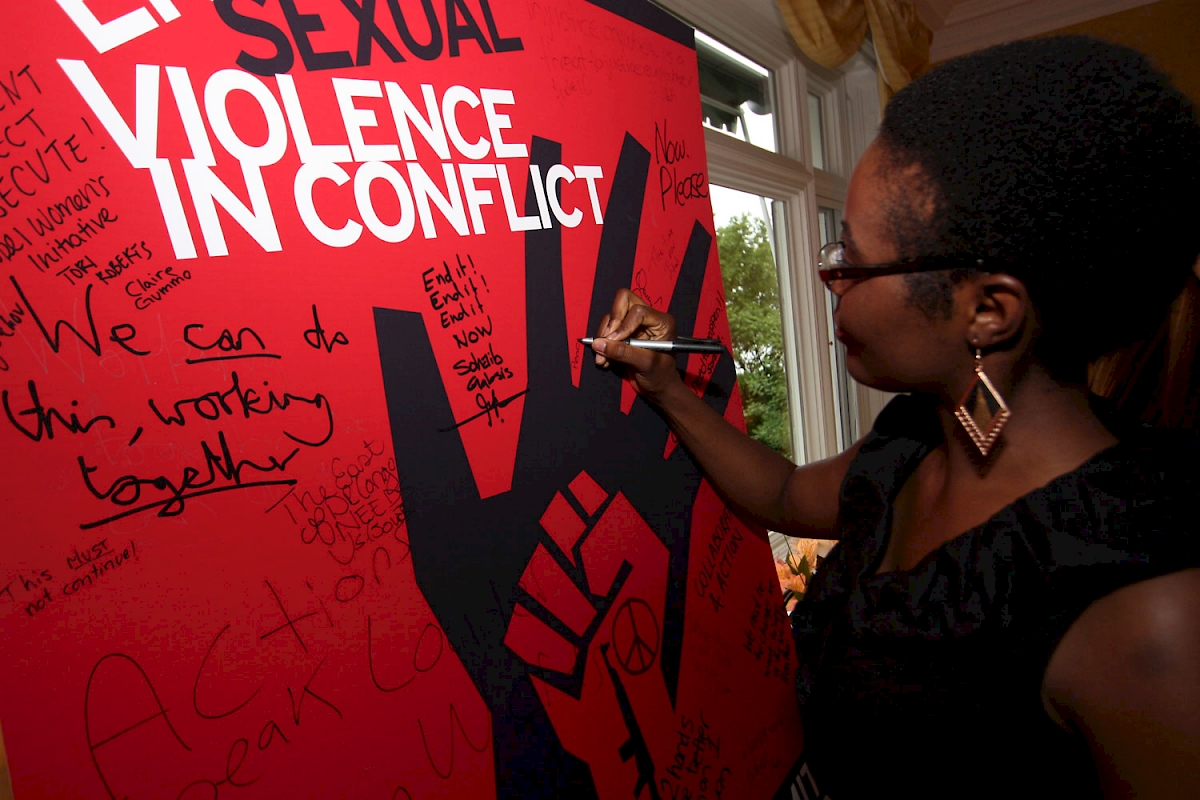

Fortunately, attention to the problem of sexual violence in conflict zones is growing and remains strong. In June 2014, the then-UK Foreign Secretary William Hague and Special Envoy for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie, co-chaired the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict. The Summit brought together more than 1,700 delegates representing 129 countries3 and focused on four main aims:

-to end a culture of impunity;

-to reduce the risk for sexual violence in conflict zones;

-to support survivors; and

-to change attitudes about sexual violence.

The conference was successful in increasing global awareness of wartime violence against women, and provided a forum to promote innovative strategies to both protect women, and prosecute crimes.

Problems in prosecution

Over the past two decades, developments in international law have bolstered efforts toward prosecuting sexual violence crimes. One of the most dramatic advances in international law has been establishing jurisprudence for rape and sexual slavery. The advent of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) expanded the scope of sexual violence crimes that can be prosecuted under international law4. However, given jurisdiction and resource considerations, the ICC is limited in its ability to prosecute the large number of sexual violence crimes that occur during conflict. Additionally, because the ICC only assumes jurisdiction over war crimes, genocide, crimes of aggression, and crimes against humanity, many sexual violence crimes fall outside of ICC’s mandate, including marital rape, gang rape, trafficking, and incest. As a result, national courts remain the primary place for holding individuals accountable for sexual violence. Governments have a moral, and, in many cases legal, duty to investigate and prosecute these crimes on a national level first, with the ICC operating as a court of 'last resort'.

In addition to the legal barriers, the documentation of sexual violence crimes presents its own unique set of challenges. These may include the assessment of young children, collection of DNA evidence, specific forms of cultural stigmatization and retribution, and misconceptions even among clinicians about anatomical changes after sexual assault (e.g. changes involving the hymen). Currently clinicians around the world provide medical assessment and treatment for many survivors of sexual violence crimes. However, they are unlikely to provide further forensic evaluations that could assist prosecutors with securing justice for survivors. Clinicians are well-placed for this role, and could ensure optimal collection, documentation and assessment of sexual violence evidence.

The role of clinicians

To be useful and effective, health professionals need to expand their traditional clinical roles and emerge as leaders and active participants in the process of securing justice for sexual violence survivors. This level of involvement would require a robust platform for clinicians to document physical and mental health effects of sexual violence which could be legally used in criminal proceedings to successfully prosecute perpetrators in their home countries.

In an attempt to establish a uniform medical-legal standard toward greater accountability for sexual violence, the Global Summit launched the International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones (the International Protocol)5. The guidelines touch on key principles pertinent to the medical documentation of sexual violence, including interviewing techniques, forensic photography, and the collection of physical evidence.

Clinicians are vital to the implementation of the International Protocol, similar to the ways in which they apply the Istanbul Protocol - a set of guidelines for assessing allegations of torture. Just as objective clinical evidence of torture increases the likelihood that torture survivors receive asylum in a country outside of where the torture occurred5, clinical evidence of sexual assault can increase the probability of successful prosecution of perpetrators. As with torture, clinicians can detect subtle findings in sexual violence survivors, including findings that do not involve the sexual organs. For example, restraint, penetration, and other forms of sexual or physical assault can leave physical evidence including bruising, haemorrhage, lacerations, and abrasions throughout the body. Where invisible wounds are present in the form of mental disorders, evaluation can be provided by clinicians who are well-trained in mental health assessment.

An adequate response from the medical community will also require innovative technological solutions. One such innovation is MediCapt, a smartphone app currently in development by Physicians for Human Rights. MediCapt converts a standardized medical intake form for forensic documentation to a digital platform and combines it with a secure mobile camera for forensic photography. By combining these components, MediCapt helps preserve critical forensic medical evidence of sexual violence, torture, and other mass atrocities. Clinicians can use the app to compile medical evidence, photograph survivors’ injuries, and securely transmit the data to their law enforcement and legal counterparts engaged in prosecuting and seeking accountability for such crimes. This tool includes sophisticated encryption, cloud data storage, high fidelity chain of custody standards, and tamper-proof metadata. In the future, the app’s data mapping feature could also assist in revealing patterns or 'hot spots' of violence, facilitating early warning of and rapid response to mass crimes.

Such technologies could be used to train physicians deployed to areas affected by conflict. Considering the scope and devastating impact of sexual violence, training in the assessment, screening, and treatment of sexual violence can be as important as that of malnutrition, infectious diseases, and other forms of trauma.

Finally, by providing an objective assessment of patients in cases of alleged sexual violence, clinicians can challenge negative attitudes and beliefs about sexual violence. They can influence the public’s understanding of sexual violence crimes, help reverse stigmatization of survivors, and encourage personal support for sexual violence survivors.

Challenges in the field

Clinicians themselves face multiple challenges, including their own biases, inadequate training, insufficient resources, and a lack of standardized protocols and practices. Additionally, important concepts emphasized in the International Protocol, such as nonmaleficence, confidentiality, and obtaining informed consent and assent of child victims, are not easily accepted and implemented, particularly in countries with divergent cultural norms.

It is critical to train clinicians so that they may undertake responsibilities throughout the legal process, after the medical evaluation has been completed. Physicians and other health professionals may be required to provide testimony about their findings in a court of law. It is worth noting that stakeholders documenting sexual violence cases to support accountability processes often experience great risk to their own personal safety or the safety of their families, especially in conflict zones or hostile environments. Clinicians, police officers, lawyers, and judges may all be targeted for gathering incriminating documentation, or even threatened or pressured to drop a case. This risk is real, and clinicians will need to be supported in this process.

Health professionals will need to work collaboratively with other professionals outside the healthcare sector, including police officers, lawyers, and judges. The Physicians for Human Rights Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones is one initiative that has observed that it is not enough for clinicians to adequately collect and document forensic medical findings. They must also effectively convey their findings to colleagues in the law enforcement and legal sectors in a manner that is accessible and meaningful in order to better inform police investigations and prosecutions. When clinicians, police officers, lawyers, and judges speak the same language, understand their respective roles and responsibilities, and work with each other in coordinated and collaborative ways to produce stronger evidence, sexual violence cases are more likely to succeed in court and perpetrators are more likely to be held to account.

Finally, though clinicians are critical to enhancing the appropriate prosecution of sexual violence, they cannot do this alone. Doctors, nurses, and other health professionals working in countries plagued by sexual violence have limited professional and infrastructural support to respond to sexual violence clusters and to adequately document these crimes. Partnerships among academic, nongovernmental, and governmental organizations are necessary to address these challenges. Building capacity within institutions in countries severely afflicted by sexual violence will require financial and time investments from the international public health community.

Scaling up

The Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict and the launch of the International Protocol has raised some real opportunities for clinicians to help address the problem of rape in war.

An adequate response must address resource limitations, confusion about roles and responsibilities, the use of medical terminology in investigations and court proceedings, and poor communication and coordination among the healthcare, law enforcement, and legal communities. Fostering the development of sustainable cross-sectoral networks can help address all of these issues. This model has been useful in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Kenya, where Physicians for Human Rights has increased the number of people trained in the assessment and care of survivors, and coordinated efforts with government bodies to scale up access to training opportunities and support. As the need for these services increases in conflict zones across Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere, these efforts can serve as a model for scaling up the implementation of effective approaches to end impunity for sexual violence. Importantly, professional investment from the medical community sends a message that sexual violence is both a crime and a public health epidemic that demands the attention and dedication of physicians and other health professionals.